Laser light is unique due to three particular properties:

Monochromacity

Divergence

Coherence

Lasers generate a very narrow band of wavelengths, typically within a few nanometres around a central line. So, a ruby wavelength of 694nm will actually be a spread between 692 and 696nm, depending on how ‘good’ the resonator is. Poor resonators will have a wider spread.

Most laser beams are minimally divergent meaning that they spread out very slowly over distance. This is why we can fire them across rooms and annoy cats and dogs and small children. We say that such beams are highly collimated.

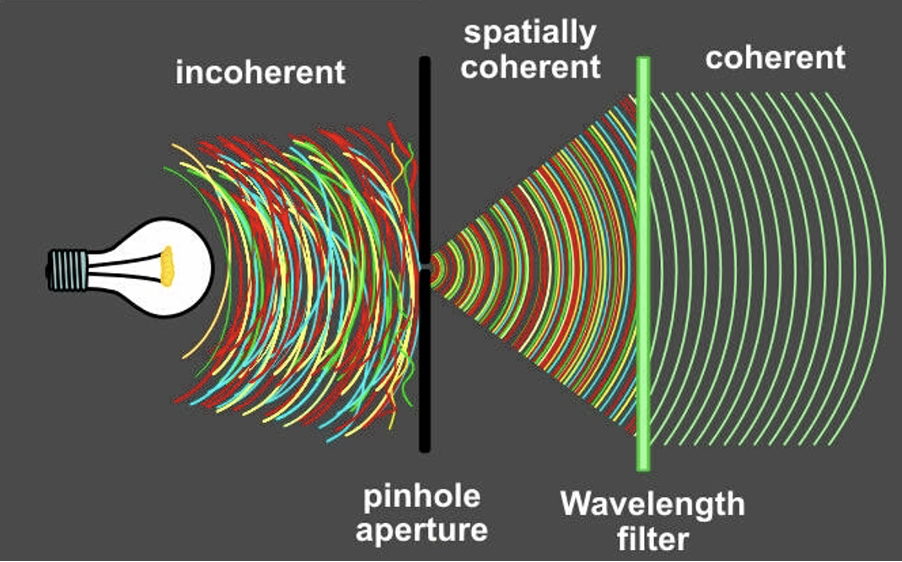

Finally, they are highly coherent. Coherence is often misunderstood but is actually quite simple. All light which emerges from very small single sources is coherent. The light waves can be spherical or planar – it doesn’t matter. The important point is that there is no interference from other light sources. Starlight is highly coherent since they appear to be from ‘point’ sources, to us.

Spatial coherence – in the above image, incoherent light is generated from the element of the light bulb because there are multiple sources where multi-wavelength light can be created. These light waves interfere with each other creating an interference pattern. When that light passes through the ‘pinhole aperture’ the waves become spatially coherent (as long as the hole is small enough). Using a filter, coherent waves of the same wavelength will emerge.

The high level of coherence in laser light comes from the fact that the source is essentially a point source inside a ‘mirror tunnel’.

[There are two types of coherence – spatial and temporal. I’ve only described spatial coherent here. You can find out about temporal coherence here.]

Ordinary light, such as that from light bulbs, fire or IPL systems, generate multiple wavelengths, are maximally divergent and are very incoherent.

What happens in the skin?

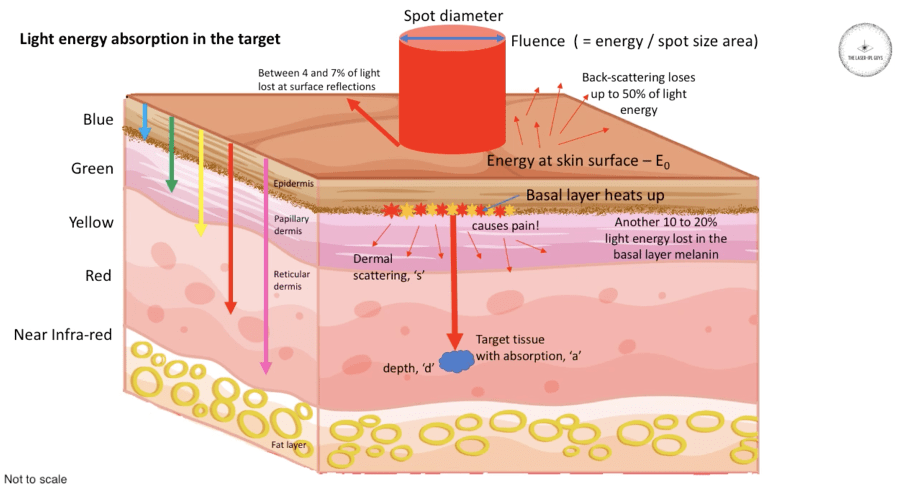

The skin is essentially a matrix of atoms and molecules. As soon as photons of light enter the skin, they begin to interact with those atoms. What happens next is down to probability – if a photon interacts with an atom which has a high probability of absorbing it, then the likelihood is that that photon will be absorbed and its energy ‘taken’ by the atom. The photon will no longer exist. It is an ex-photon…

If, however, the probability of scattering that photon is high, then it will likely be ‘rejected’ by that atom and sent on its way, to the next atom, where it will be either absorbed or scattered.

There is nothing else which can happen to these photons – they must be either scattered or absorbed. There is no ‘third path’.

I posted about ‘light in the skin’ earlier this year – https://mikemurphyblog.com/2023/04/26/what-are-the-differences-between-lasers-and-ipls/

You can view the above video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fnFDgEVUQXc&t=251s

So, when laser light enters the skin, it also undergoes these two processes. Now, this is very interesting because something quite fundamental occurs.

Firstly, when photons are scattered, they usually take a new direction compared with their initial direction. As a result, a laser beam rapidly becomes highly divergent, just like ordinary light. This is purely due to the many, many scattering events.

Secondly, each scattering event is essentially a new source of photons (in reality, photons do not ‘bounce’ off atoms. They are absorbed and a new photon is generated, which emerges in a new direction). So, the coherence is lost rapidly too since each scattered photon comes from a new source.

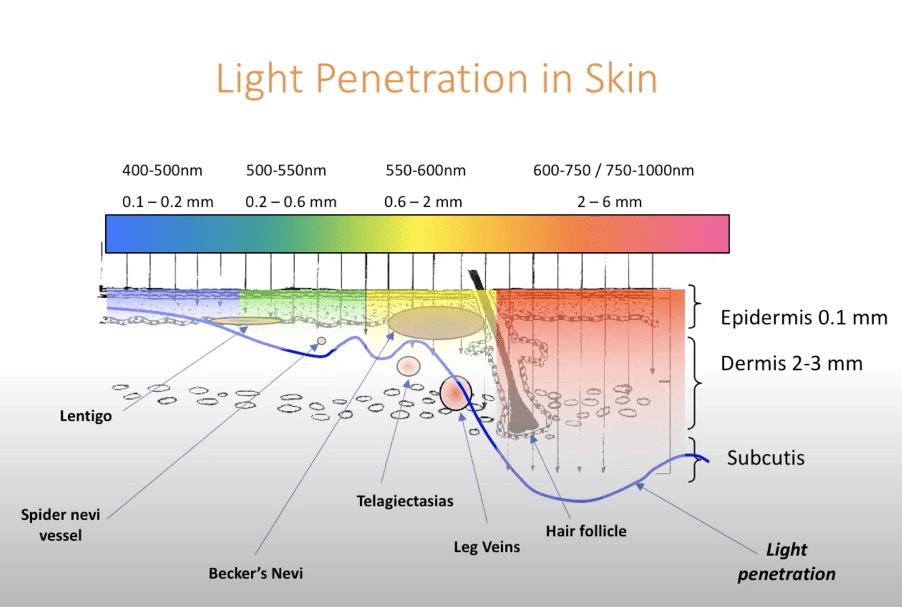

Thirdly, the skin has a higher refractive index compared with air. This induces a change in the velocity of the light – it slows down (fractionally). But the light’s frequency is set at its source (inside the laser cavity) and cannot be changed. As a result, the wavelength must change – this is the principle of refraction. If the light is slower, then the wavelength must decrease. Assuming an average refractive index of around 1.36 to 1.41 for the dermis, it’s easy to show that the Nd:YAG fundamental wavelength of 1064nm will change to around 768nm in the skin, while a diode wavelength of 808nm will drop to about 583nm.

(I’ve written a wee paper on this issue which I really must get published…)

You can view the above video at https://youtu.be/iafTDXYiEcY

So, when laser light enters the skin it loses its coherence, its minimal divergence (collimation) and its wavelength changes due to refraction. I would argue that this light, inside the skin, cannot now be considered as ‘laser’ light! It has lost two of its unique properties, and its wavelength has changed.

Can a monochromatic beam of light be called ‘laser’ when it is highly divergent and incoherent? I don’t think so.

Conclusion

We have seen that laser light changes dramatically when it enters the skin. It loses two of its main properties, and its changes colour. However, it maintains its energy content, and it is this that makes it useful for treatments.

The important point here is that the type of light which is fired at the skin is not important. It is the energy/fluence which determines the clinical outcome. The light is merely a method of transferring that energy into the skin constituents.

When absorption occurs in melanin or haemoglobin, it doesn’t matter whether the light energy is in the form of a laser or not. It is quite irrelevant. It is the total number of absorbed photons (the energy) that matters; not their source.

So, what is the difference between lasers and IPLs? Mostly just the price!!

Hope this helps,

Mike.

Come along to our MasterClass in Luton in September and find out how to apply these technologies properly to the skin. Email us at DermaLaseMasterClass@gmail.com.