When light enters the skin the photons immediately encounter atoms and molecules. With each encounter there is a probability that each photon will be either absorbed or scattered. The skin is a highly scattering medium, so the probabilities of scattering are usually much greater than the probability of being absorbed (in most events). Some of them (around 5% or so) are reflected straight back, out of the skin.

Consequently, most photons are scattered many, many times before finally being absorbed by an atom, somewhere…

One of the main consequences of all this scattering is that the direction of each photon’s travel changes. Many are effectively ‘turned around’ and they may leave the skin altogether – this is called ‘back-scattering’. Monte Carlo simulations of these events show that up to 60% of all the light entering the skin may be back-scattered out of it completely! This does depend on the wavelength.

This results in an interesting phenomenon – the fluence just under the skin’s surface can be significantly higher than the fluence fired at the skin’s surface.

Fluence variation with depth

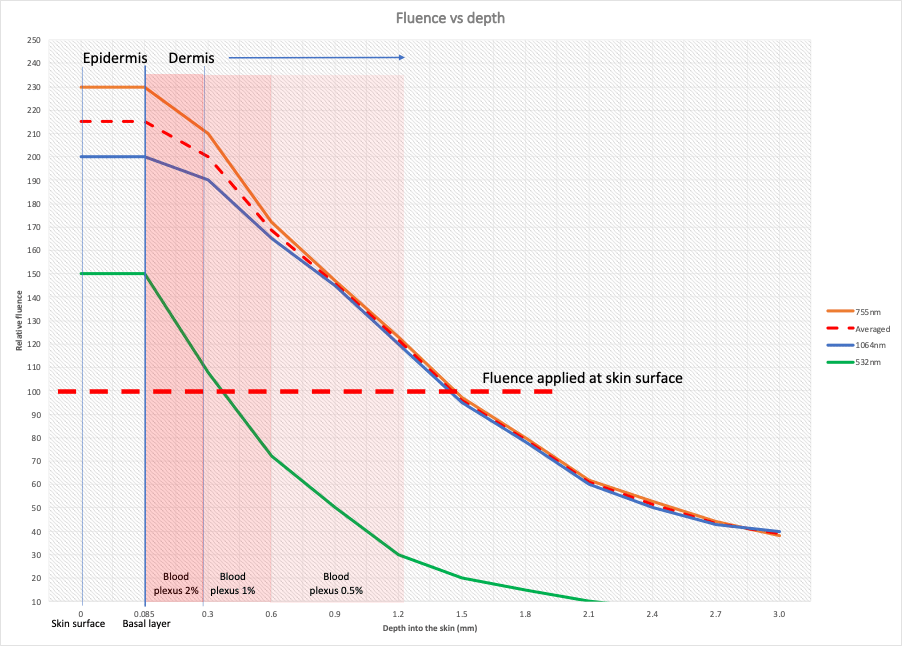

My colleague, PA Torstensson, generated a Monte Carlo model to calculate this change in fluence in the skin for a range of wavelengths. The graphs above show his results.

He set the incident fluence (at the skin surface) to a level of ‘100’ (this is an arbitrary choice and can represent any fluence required) – this is the horizontal dotted red line in the above. He looked at 532nm, 755nm and 1064nm. He also added in the averaged values of 755nm and 1064nm (the other dotted red line).

As we can see, the fluence for both 755nm and 1064nm is higher in the top 1.5mm of the skin, compared with the fluence fired at the surface. This is simply because the total fluence (as shown here) is the combination of all the photons travelling deeper into the dermis and those photons moving towards the surface, after being back-scattered. Even the 532nm light increases in fluence down to a depth of around 0.4mm.

This is clearly not intuitive at all! We don’t imagine this might occur because we don’t really know how photons behave in such a medium (without such calculations and modelling)!

The above curves show that the 532nm wavelength can be as much as 1.5 times the incident fluence, while the 755nm and 1064nm wavelengths can reach as much as 2 to 2.3 times the original fluence. These two wavelengths exhibit very similar fluences once they reach a depth of around 0.9mm – in other words, there is no significant difference between them below this depth (which will surprise a few people!).

What does this mean in treatments?

Most laser/IPL treatments in the skin depend on the rise in temperature within the intended target (melanin, blood, tattoo ink). That temperature rise is dependent on the absorption coefficient of the target (which varies with wavelength) and the fluence which hits that target.

Clearly, the temperature rise drops as we go deeper into the dermis, since the fluence is lower there. From the above curves, it is obvious that the highest temperatures will be achieved near the skin surface, where the fluence is highest – for any wavelength.

As I said, the temperature rise also depends on the absorption coefficient of the target, μa – this determines the probability of a photon being absorbed by that target. If μa is large, then the likelihood is that the photon will be absorbed, which will add to the temperature rise in that target. We should note that μa is very dependent on the wavelength.

So, if we need to attain some particular temperature in our target, then we must be sure to apply sufficient fluence at the skin surface to ensure it is achievable. The results above indicate that this may be achieved by proper selection of the fluence at the skin surface. Increasing this will increase the amount of available energy at all depths. This means that we may need to use higher fluences to reach deeper targets.

But, and it’s a big ‘but’, there is another factor which must be considered – the pulsewidth.

The importance of pulsewidth

When light energy is absorbed by anything, some of that energy will be converted into heat energy, which raises the temperature of the target due to vibration.

However, if the energy pulse is relatively long, then there will be time for some of the heat to ‘leak away’ from the target while it is still being hit by photons. This can easily occur with millisecond pulsewidths since many targets are very small, and lose heat rapidly. The longer the pulsewidth, the more heat will escape.

This means that the maximum temperature attained in that target will be lower than if a shorter pulsewidth was used (where less heat will be lost). Given that some particular temperature rise is the goal of most laser/IPL skin treatments, this suggests that shorter pulses are generally more useful.

This is basically true in most treatments, but in others we prefer longer pulses – they make irreversible denaturation more likely (but that’s a different discussion…). In tattoo removal, shorter pulses are much better. Shorter pulsewidths require lower fluences to achieve the same end-result.

Summary

This post is a bit more scientific than my usual stuff, but I hope it makes sense. This topic of light propagation in the skin is quite complex, as you can see. In essence, the success rate of any treatments depends on the required fluence hitting the desired target, at various depths in the skin.

But it must also be of the optimum wavelength to increase the absorption of light energy. Plus, the pulsewidth needs to be sufficiently short to minimise heat losses into the surrounding tissues, during the pulse.

Hopes this helps a bit,

Mike.

Our next MasterClass will be held in Glasgow on February 4th and 5th. If interested in joining us, please write to lisa.dermalase@gmail.com.